CVE Actually Does Trust Open Source Implicitly and That Is a Problem

Last week the Security Developer-in-Residence at the Python Software Foundation Seth Michael Larson said he loved an article from Open Source Security. The article touched on an important issue with the CVE system, though, coming from an author, Anchore’s Josh Bressers, who seemingly has no idea what he is talking about. CVE is a system that is supposed “to identify, define, and catalog publicly disclosed cybersecurity vulnerabilities”, with “one CVE Record for each vulnerability in the catalog.” What CVE actually is is a prime example of how much of the security industry is a scam. As the catalog is filled with information that is often misleading to outright false and lacks the basic information needed to make the information useful or to vet it.

The post at Open Source Security claimed that something being done by the Node.js project “is against the CVE rules” and that “[t]his is important because it can frame some of the discussion we see.” Those claims are not backed up by anything in the post or what is linked to in the post. The reality here is even if something is against the rules of CVE, the people running it have been very clear in their actions they don’t care if it is done by something they allow to submit information directly in to the catalog.

Part of the posts claims that CVE doesn’t trust open source:

Every time the open source crew suggests maybe we could all work on making some new pants together, all the other groups laugh at them and explain there’s no way a group of random people can work on something as complicated as vulnerabilities. It’s just not realistic, how could we trust that data?

The conversation goes something like this

CVE: “How could we trust the data a bunch of random people put together?”

Open Source: “We created Linux, that’s way more complicated than your data”

CVE: “But can we trust this Linux thing?”

OS: “You’re running Linux right now”

CVE: “I’m hearing that we can’t trust community data”

OS: “your data is terrible, nobody can trust it now”

CVE: “This open source thing sounds like a fad that will die out in a few years”

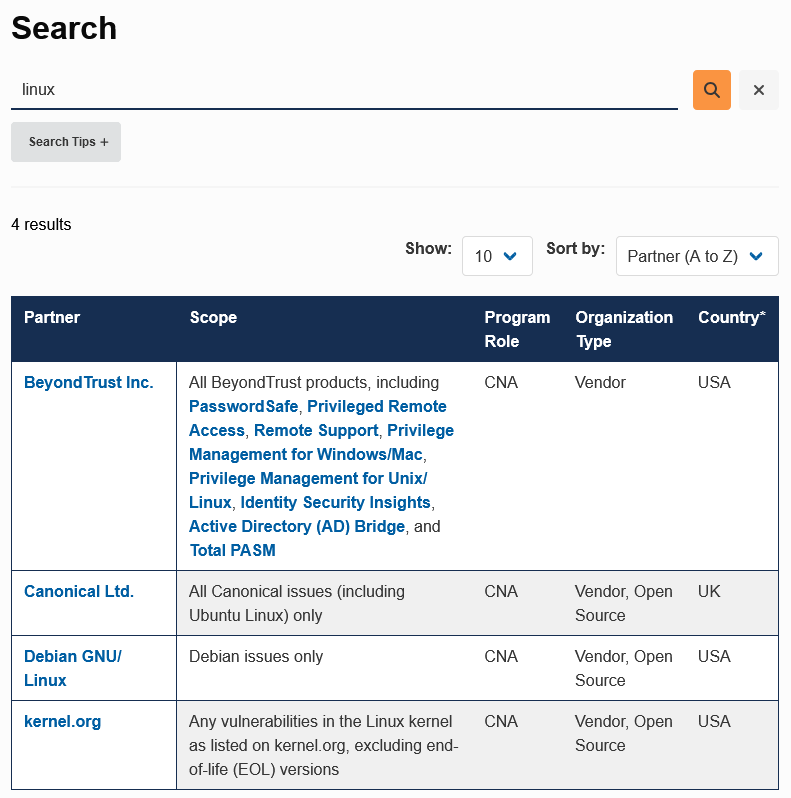

If you look at the list of entities that can directly submit information in to the catalog, CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs), not only are their numerous open source projects included, but the Linux kernel is itself one:

Seth Michael Larson should know that, since he wrote the Python Software Foundation’s post about them becoming a CNA as well.

Basically, anyone can become a CNA as long as they have a website. Trust isn’t required at all. The only requirements are:

- Have a public vulnerability disclosure policy.

- Have a public source for new vulnerability disclosures.

- Agree to the CVE Program Terms of Use.

Having software developers have control of vulnerability information is problematic. Developers often are not honest about vulnerabilities. So the information they provide isn’t trustworthy by default. That becomes a lot more of a problem with CVE because information in CVE is treated by the security industry as being reliable despite its information often times not being accurate.

Software developers have a possible interest in underplaying vulnerabilities, but you would assume not overstating them (but maybe they would), but CVE isn’t limited to software and hardware developers. Third-party security providers who have an interest in inflated claims of quantity and severity of vulnerabilities are also CNAs. They are sometimes rather honest about their lack of concern for the accuracy of information they place in to the CVE system.

Why does the security industry treat the information as reliable when it isn’t? One simple answer it allows security providers to cut corners. The company the author of the post works for, Achore, for example, can claim to provide continuous vulnerability monitoring without doing the expensive work of vetting the information they are providing their customers or paying someone else to do that:

The security industry is able to make a lot of money off of work they haven’t done. The end result of this isn’t good, since what you find when you actually do the vetting is often the vulnerabilities haven’t been properly fixed or haven’t been fixed at all. That can lead to widespread hacks of vulnerabilities that were never really fixed.

If CVE were to become a reliable source, then open source providers (as well as everyone else) would need to not be trusted without verification. In the meantime, you can find honest providers who don’t rely on CVE information, since they know it isn’t reliable.